Gallery of Exhibits

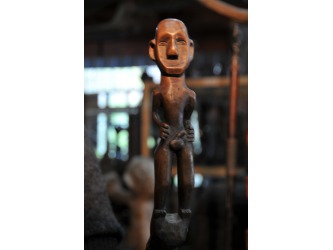

The religion of the Ifugao people is based on ancestor worship and the veneration of spirits and gods of nature; they are pagans. Rice deities are particularly revered. These bululs are activated through ritual, the bulol guardian figures are believed to contain spirits capable of ensuring abundant harvests, increasing rice yields and protecting against catastrophe. Shaped like a rice mortar, the distinctive base of the sculpture is a visual link to its spiritual purpose. The pairing of male with female is a fundamental feature of Cordilleras ancestral art. These bulul guardians represent the harmonious union of opposing elements, the protection of communities from malevolent spirits and the promise of good fortune. Carved from auspicious red sandalwood, these sculptures are differentiated by their distinct genitalia, alluding to fertility and abundance. The figures have a rich patina of sacrificial blood and smoke resulting from their use in religious practice and life-cycle ceremonies.

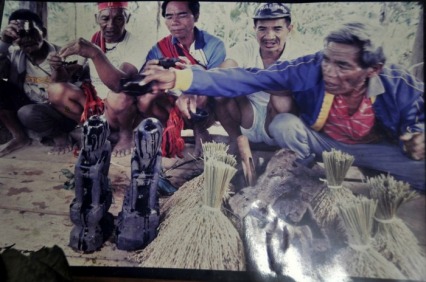

Photo: Ifugao Priests

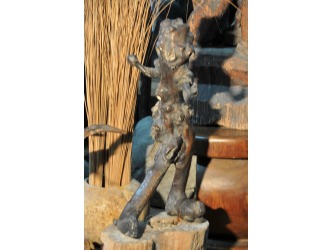

Dancing with a Pig

A sculptural tableau of a pig and a Tino-Too-Oo figurine who represents a bride dancing on her wedding day; her face expresses a delight that shines through the crudeness of the carving. The undelighted pig, portrayed posthumously, has already been butchered and served up for the wedding feast. Iwak Tribe, at Kayapa, Nueva Vizcaya; circa 1960

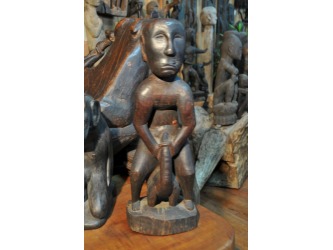

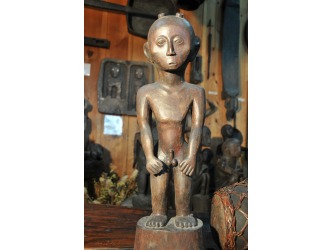

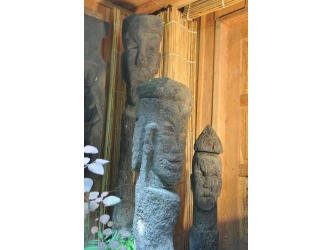

Two Idols

Two Idols fully primed with a power found in varying measure in nearly all Cordilleran Figurines that manage to be aesthetically and spiritually engaging. Including hundreds in this museum. It is a power in inherent in the art of cartooning, at which Cordilleran carvers are masters. Their sculptured beings resemble so many old time-comic strip characters (or today's counterparts on TV), less humans than unclassified hominids, limbs shaped by an evolution more rubbery than ours, faces simplified , as enigmatic as sweet potatoes- A physiognomy that perfectly suits the idols to serve as recipients of the pagan prayers. In a prayer session the supplicant hunkers down before a family god let, chants and divines in the idol's bland features exactly the hoped for response. Encouraged, the believer either goes forth and works to help make the prayer a reality, or waits for the providence to provide. For our part, we aficionados of the idol as a spiritual are face the regent from the sky world and allow ourselves a flash of belief, a "Pagan Moment".These idols are replicas of antiques in the home and lifelong service of Banaue's foremost pagan priest, GUMUWANG DALIPOG. Of course he will never give them up to be institutionalized. But the copies deserve a place here: They have things to say to us.

An Inherited Veneration of Owls

Certain beliefs and imagery scared to the pagan terrace farmers in these mountains originated in the Philippine lowland or even overseas millennially distant in time. A fearful reverence for owls is one such tenet of the mountaineers' paganism. In Ifugao these gnomish and unnerving birds have been venerated graphically by carving their heart-shaped facial outline on some of the tribal granary deities (Bulol). In Ifugao, as elsewhere in the Philippines, the night cry of the owl near someones home portends the imminent illness or death of someone in the family or the vicinity. In one know Philippine lowland location the owl; from the prehispanic era until a few years ago; reigned as a God, one whose centuries' old image as alighted here before you in the form of a disturbing creature known as the Santo Kulago of the Guiuan; the owl saint of Guiuan. Carved in that Eastern Samar City some 1400 kilometers southeast of Ifugao; Early in the Spanish epoch; of Molave, one of the hardest of native woods, the statue bears the feathered body of an owl combined with a much eroded human face and head, crowned blasphemously with a christian cross. It is an easy presumption that the carver had converted from Animism to Catholicism, but tepidly. He, as do a majority of Ifugao today, thought it political to practice a divided loyality, half animist and half christian. But he, alone with the cult that grew around this idol and carried on its Dionysian celebrations, kept all of this secret fromt eh resident Padres (priests) during the "Spanish time". The cult remained populous and joyful until one year in the 1980's when two children the Owl Saint's flock died from an unknown illness. The bird was thought to have been the cause as a punishment for some offense to it. Caution: Think kindly of the Santo Kulago of Guiuan; since he or she reads thoughts no doubt.

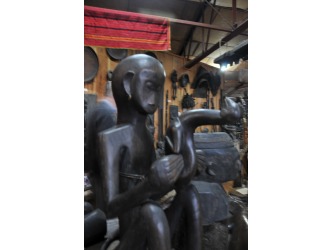

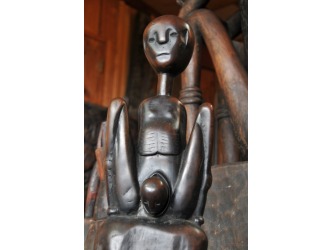

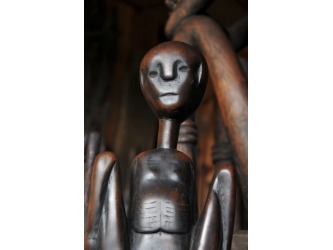

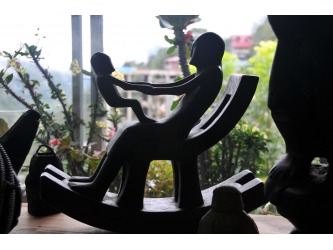

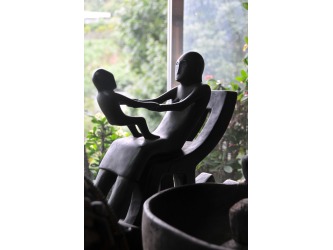

Mother and Child in Two Guises

One of these guises is subtle study in burl wood; close examination is needed in order to make out its' two sketchy human figures. This startlingly modernistic work is by Miguel Bulayungan, a Banaue villager who had never seen an example of modern art except for this and others of his own invention.The other mother and child are more or less monkeys. The carver is the richly inventive Anton Ambojnon of Banga-an village. A grandfather, he might by now have an international following if anyone had ever collected his art and presented it as a body of work. As things are, his occasional pieces (carved whenever the mood strikes him, in the between the duties of rice farming) have been purchased, scattered and effectively consigned to oblivion, by dealers who have not bothered to get his name. This story of an unrealized career applies as well to several other creative carvers in this collection.

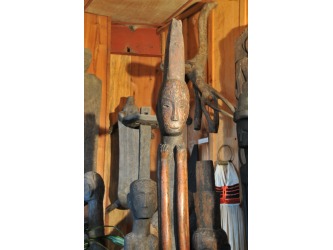

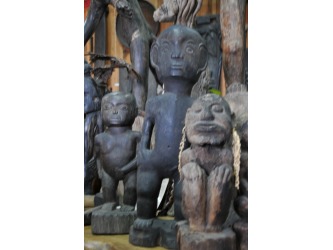

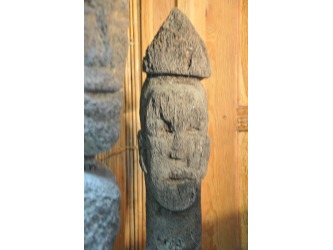

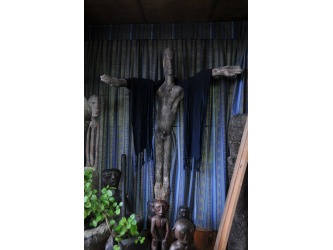

Village Idols

Pictured here is one of the two large scale idols who went to Europe and never came back (other not pictured here).He is an example of the more imposing Cordilleran sculptures that were among the first to be shipped to Europe during the 1960's and 1970's heyday of the exportation of the region's artworks- while they lasted. These mountains have been pretty well stripped by now with the major exception of the thousand-plus pieces in this room, assembled here with a sense of mission: save for the country whatever great works of the carvers' art can still be saved...The two village idols (only one pictured here) who ended up in Europe were - fortunately for our understanding of Cordilleran tribal sculpture- exactly replicated by a carver with a photographic memory, Noel Balenga, who, as a boy, helped his father lug the originals down the mountain trails to eager dealers, and to exile.

Ifugao Priests (Mombaki) Baptizing Granary Deities

Baptizing and re-energizing a bulul pair with the blood of sacrificed pigs, as a feature of annual harvest time rituals and festivities. One of the priests (a mombaki in their language) pours the blood from a coconut shell cup, which he has removed from its keeping-place in a ceremonial box (an innama) shown opened in the lower right in the photograph.

Below is a photograph of Apomuog of Banaue, a mombaki, preforming a ritual. Photo taken in 2008

Chimeras

A man-dog; a man-frog; a man-butterfly; a man with a beastly Willie; a woman with goat horns and crab legs; a crocodile partly human; duck and snake; the Cordilleran chimeras assembled here (not all photographed) descend from an ancient and illustrious line of tribal imagining. Tribal societies have always delighted in dreaming chimeras into being, in hundreds of human-animal conflations. And when tribes arose to become great civilizations of antiquity, they brought their beloved chimeras with them, sometimes even deifying the grafted creatures- as did the Egyptians with their pantheon of animal-headed, human-bodied gods. yet the Greeks, rather than worshiping their centaurs and satyrs, democratized them as being pretty much people, in a rich mythology ascribing to them humanly good deeds or deplorably human behavior. And int he mountains of northern Luzon, chimeras are yet being born of a visionary sense that remains vigorously alive, vigorously tribal.

This man-frog, by Noel Balenga of Banaue, pictured here on the left, was a vision had by Noel who having spied a big frog hunkered beside a mountain trail, at ease but alert, was struck by a similarity in the amphibian and in tribal elders resting in a village's meeting area, hunkered down, leaning forward, easeful but watchful. In his carving Noel hybridized these two apparently compatible life forms.

Ifugao Bulul (Rice God) portrayed as a priest

examing a chicken's gall bladder in a Ritual

The position of the gall bladder augurs the accord or the disfavor of the spirits toward some proposed enterprise. If the organ lies outside the folds of the chicken's liver then it will be safe to go ahead with the weeding, the business transaction, the journey or whatever. But if the gall bladder is hidden within the liver, cancel the enterprise. To proceed would result in terrible retribution.

Prayerfully Pregnant

A sorority of pregnant wives- portrait statuettes carved by their husbands- likenesses recognizable at least to the carvers. These carvings were prayed to with a passion probably equal to that of a devout Catholic addressing a wooden santo in a household shrine. The Christian might plead (in some such words); Saintly spirit enter the santo, hear our need and grant us easement. Correspondingly, the pagan prays to the Sky World spirits, coaxing them to inhabit the effigy of the mother-to-be, and ease the pregnancy of the actual women.The tallest of the statuettes (one of Bontoc tribal origin, though curiously suggestive of Polynesian imagery) clasps her hands in a gesture of prayer that some Cordilleran pagans share with Buddhists and Christians....The little figure with the chicken came from the Kalanguya people, and we are informed by a man of the tribe that the tableau's message is, "the chicken will be sacrificed so the baby will come out nice"... the legless carving (of Kalanguya type) shows the mother-to-be dressed up with the necklace of heirloom beads, while baring fierce teeth to ward off any evildoer...The figure whose eyeballs are plainly boys' play marbles (Bontoc) is a wife's portrait combined with that of a tribal cult figure, a woman with unusually wide-set eyes, who had, in local belief, special powers to safeguard pregnancy.

Kinabigat (King Post)

A support post for the peak of the steely pitched thatch roof of a traditional Ifugao house (such as these located in the museum's garden). These kinabigats, are carved in the form of a protective idol- a bulul.

The Ages of Bulul

(from left to right in photograph)

At birth (far left): A bulul (Ifugao granary deity) newly carved of mahogany, before the idol's first baptism and empowerment by blood bath.

Middle Aged (second from left): A bulul after about 50 years of service, and a yearly application of blood. This idol is genuinely old; the one to the left is a replica)

Senior Citizen (third from left): A bulul a century-and-more-old. Note the heavy encrustation of blood from annual applications during harvest-time rituals. (But not all families anoint their bulul with blood).

The Undead (far right): Some Ifugao families carry on revering and fearing, propitiating and praying to their heirloom bulul as living members of their clan, until those idols crumble to pieces in extreme old age. Such is the life story of this disintegrating, two-century-old bulul, retired at last in 2002.

Pickled-Meat Box with a face

A Bagbago tribal carving figuration with a ngilin (a spirit face). The eyes are heirloom agate beads; carved of the Pine by Lominyo of Payen, Quirino, Ilocos Sur, in the 1040's. Sold by his son in 2004. The artistry might as well be that of an African tribe- there's quite a resemblance here.

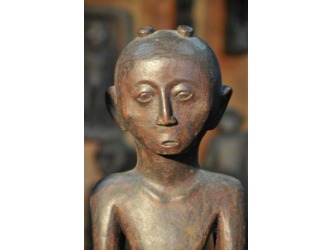

Four Divine Dwarfs -Unano-

Dwarfism is one of the several physical conditions considered by the pagan Bontoc and Ifugao to bestow a measure of divinity on the bearer: surely he or she, in having been touched by the gods, possesses special spiritual connections, a status worthy of revering with a carved effigy and with prayers sent up in care of the carving. People with certain mental conditions (microcephaly and less profound degrees of cheery simpleness) have also been effigied and engaged as spiritual go-betweens.

Six Streamlined Jars

Modernistic but not modern. Streamlining appeared in Ifugao sculpture in the form of these wooden jars as early as about 1900, before the coming of aviation and the revolutionizing effect of aerodynamic formulas of the 20th century design in general- before Bauhaus, before Art Deco, before Scandinavian Modern- perhaps before anything of the kind anywhere else. Of course almost nobody outside the locked mountains of Northern Luzon of the time knew of this advent of streamlining in the artistry of humankind. Inspiration for the jars' come from river smoothed stones, hydrodynamics exerting exactly the shaping force as that of aerodynamics, and bringing on the same contrarily soothing yet stimulating sense in ourselves.

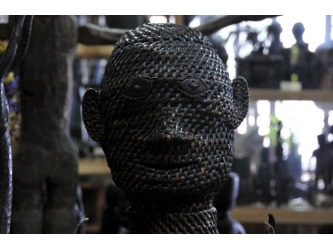

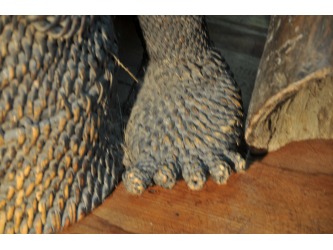

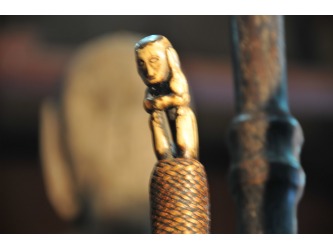

Three-in-One Idol-Seat-Bin Sculpture

Rice terrace farmers, practical-minded mystics that they are, have delighted in adding usefulness to their religious art. These Cordilleran farmer-artists have carved their deities on at least a hundred different things they've made and used- tools, implements, containers, furniture, accessories- as we know by having counted just that many kinds in this museum. The combination of religion, art and utility in single objects, conservative of time, space material and effort, has reached its culmination in the carving (or weaving) of such three-in-one sculptures as you see: an idol made of rattan, complete with a seat in the readiness for a deserving derriere , plus a bin for sweet potatoes; Gatan, the rattan man, as we call him, would be carried outside to participate in a Kalanguya Ifugao family's festive occasions.

The Snugglers

On chilly winter nights many farm families in these mountains sleep as close as bananas in a bunch. Snuggling is clearly a dear memory for the Ifugao grandfather who carved this tableau of himself and his family, when the children were small.

Tinagtago Idol Giving Birth

This was the child-bearing posture preferred by Cordeilleran mothers in tribal times. The carving, circa 1900, is by Alicdang of Sagada. Sold by his grandson in 1987 under the usual circumstances, a family's urgent need for cash. The seller's mother, eightyish lamented the departure of this tanagtago which she had held as a doll when she was a small child, and which, afterward, she and her husband had placed beside their bed to guard them throughout the night.

Pig on Dais

Carved as a deity, this pregnant sow demonstrates that few things in the world of Cordilleran rice farmers are more crucial and more sacred than pigs. The skillfully realistic statuette served as a focus for prayers. "Oh spirit mother of pigs, bring us many healthy piglets".

PIG EFFIGIES

Prayed to- or through-with the hope that prayers would bring large an healthy litters of piglets. Early to mid-20th Century.

Ceremonial Stool (Dalapongan)

A seat - of - authority for an appointed elder of the Applai tribe, a man who settled marital disputes (usually over the division of property of a couple divorcing because of childlessness). With its somber blackness (from sooty fires), its deltoid wings and hollow sockets, this construction of bones, wood and rattan suggests a bovine deaths head or a crippling stingray, certainly nothing cozy to the mind or body.

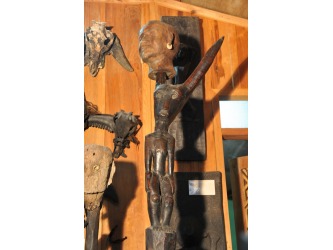

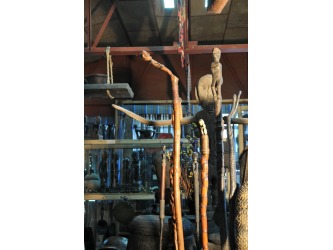

Figurated Posts

Figurated Posts: Called Hogang, these free spririt-figurated trunks of tree ferns were placed as boundary markers at the edges of villages and home properties.

Black Phallic Stone: Caution: in tribal belief, merely touching this stone may induce pregnancy. The stone phallus is one of the several large-size, columnar shapes fo solidified lava, completely natural and uncarved, that are considered by Ifugao pagans to be sacred; as such, these stones are perhaps the rarest of tribal artifacts in the province.

Granite Alter with the Face of Halocoy: An alter dedicated to Halocoy, spirit of the locusts. In front of this alter ceremonies were performed yearly from about 1920 until 2000 to dissuade swarms of locusts from attacking the fields of rice.

An Idol Named Alawah

Carved in the 19th Century, in Poitan village near Banaue, where the idol rose in the people's regard to be become the King Bulul- the community's most revered granary deity. Nowadays, Alawah is believed by many Ifugaos to be the most powerful bulul remaining in their province, bereft of so many by the international trade in tribal sculpture. In decades past, Alawah's imagined deeds of power and wisdom inspired a number of legends, the most widely recited of which has to do with the origin of his name. He become Alawah on a day in 1902, during a raid on Banaue and vicinity by marauders Burnay and several allied villages. Banaue won, taking most of the estimated 200 heads lopped off that day. But during the battle, so story goes, Pindug, the sister idol of our legendary bulul, was speared by a raider. In response, the village's cadre of idols shouted "Allawahon!" - "stop him!" "Alawah" is a contraction of that shout. And indeed he stopped the raider dead, yet without leaving a mark on him. This entirely real death, which seemed uncanny to the Poitanans, was likely caused by a heart attack.

Dancing Bululs

Ifugao granary idols in ritual dance posture, a specialty of Kiangan villagers. Unlike the man and wife bulul couples carved in other Ifugao villages, dancing bulul are singletons. Their outstretched arms represent those of real-life dancers who imitate the flight of swifts or swallows; a beating of wings followed by an effortless glide with complex twists and turns.

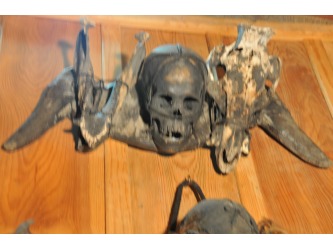

Skull-Plaques (Changit or Hangit):Sculptures of Heads-Hunting

For centuries the tribesmen of the Cordillera stalked their enemies, lopped off their heads and took them home. Trophy heads, turned into skulls, won the head-taker the respect of his fellows and the admiration of women. Of the six tribes that took heads only the Ifugaos displayed them in works of assembled sculpture such as those you see above. Head-hunting raids, sanctioned and carried out by entire villages, toke place until 1913, the year when American Forces who governed the mountain tribes after the Spanish-American War of 1898, finally persuaded village leaders to give up communal decapitating. But unsanctioned head-taking by individuals continued until well after 1950.

Below is photograph of a Post for Freshly Cut Heads( top center and right:An early 20th century carving brought from the mens' meeting area within a Bontoc Village. Heads of enemies were impaled (as you see), gloated over during several days of celebratory dancing, feasting and drinking; afterward, boiled, de-fleshed, and hidden away in a room forbidden to all but the elect.

Below Dancer's Mask "Pamadi-Gna (bottom left): Fashioned early in the 20th century by Bannac, one of the line of men bearing that name who have lived in Bayo-wan, Mountain Province. The mask is made of the pelvic bones of a water buffalo bound with rattan and decorated with carved heads of sacred kalaw birds (horned bills). Early on, in head-hunting days, the mask was likey to have worn during blood raids and at victory dances afterward. In more recent decades, Bannac men have danced with the mask at harvest times and weddings. The family became christian in 1990 and retired the Pamadi-gna.

Dismayed Chair

The carver Benito Binusnie of Bayongan village portrays his wife, who has been grumbling that life is nothing more than dawn-to-dusk labor in a rice field, as a victim of a strange transformation: her right leg is mutating into a ga-ud, the long-bladed wooden spade (there is an example on display in the museum) still used instead of steel by a few farmers to turn the soil of the terraced fields. She is understandably dismayed but may have been expecting as much.

Pamahan

I

Ifugao ceremonial bowl embraced by a bulul

Sokyop - hunter's skullcap

Headgear of this type, carved with a semblance of a human face, or carved plain and featureless, or with a carved animal head crest, are (or were) accouterments of hunters in the Barlig vicinity of Mountain Province. In centuries past, sokyop were worn during dances by hunter's celebrating a successful kill. But now, the deer and the feral pigs they pursued are of a scarcity approaching extinction, and the hunt itself has been given up. Today's would be hunters in Barlig are like the rhinestones cowboys of North America and Australia: they celebrate the memory of a former glory. They honor the tribal past of their village at sunrise on special days called teer (pronounced too-er). They reminisce about the chase and the thrusting of the spear- the older men still remember the hunt first hand. And now at the mens' meeting area the hunters-in-spirit fill a skullcap with rice wine and pass it around. Each man downs a swig of the wine. They sit for two or three hours. Then they all go home. No work is done during the day of teer.

Ultimately Small Hagabi

When inspirited by priests' prayers and major animal sacrifices, tiny representations of Ifugao prestige benches (Hagabi) such as these, are believed to possess curative powers at potent as those of full-size (13 foot long) Hagabi or intermediate miniatures (2.5 to 3.5 feet long), examples of which are on view in the museum. One of our tiny Hagabi was carved together with a small idol (bulul), the two to be used in tandem as healers (the bulul represents members of the sick person's family at prayer). The other ultimate miniature was carved by a priest/medicine man who kept it i his sacral box (innama) with other magical medications, and carried it to the homes of constituents in need of treatment. The deep, glossy patina on this tiny artifact comes of many years of caressing the wood between thumb and forefinger in the manner of Catholics and their rosary beads, giving tactile presence to prayers.

Ifugao Wedding Portraits

Carved by the bridegroom or by a relative at the time of the marriage, displayed in the newlyweds' home thereafter to keep their union fresh in the minds of the spirits, with the hope that they will stay on the alert to protect the couple. Though uncommon in most communities, carved wedding portraits have been a usual feature of Kalanguya Ifugao weddings- with head to head examples of the portraits a Kalanguya specialty. The clear display of affection in these tete-a-tete statuettes is decidedly rare in the tribal art of the world, where any evident display of emotion is generally a face of threat or rage.

Dancing Tinagtago

Far less balletic in appearance than pugilistic; much like a pug-ugly heavy weight who is about to throw a right -cross or maybe gnaw a chunk of his opponents ear. Red narra, with boar's teeth for eyes and sea shell teeth. Carved by the farmer Tamaling of Quirino, near Tirad Pass, Mountain Province; in about 1960. Tamaling has patched up cracks in the idol with the sticky sap of the A-as Tree. The tinagtago is performing the Tayao, a dance of mourning at the time of a death in one's family, and also a dance to cure illness.

Ifugao Priests' Ceremonial Boxes

The lidded boxes (innama, innaho) scattered here in the museum on a slab of mahogany are of a kind used by Ifugao priests (mombaki) in conducting the pagan ceremonies of the rice harvest (punbot-an) and of the curing of illness (dinupdup or doyaton). Such a box and its contents of scared objects are roughly comparable to the chalice and other sacramentalia carried from home base by a Catholic priest on duty. The Ifugao carved counterpart takes many forms: some of the boxes are square with either plain or animal-figurated lids; other (rarities) are figurated with idols in human form; still other boxes are oblong, with stylized pig heads or dog heads as handles. Yet there are boxes that follow no style at all, but are the unique inventions of their carvers. The largest box on display at the museum has a 20.5 inch idol seated on its lid, was designed as a sty-at-home innama; massively heavy, it probably never left the premises during its century of service; while the smallest of the boxes (only 3 3/4 inches high) was made for practical portability to member s of the mombaki's congregation who have lived at some distance along mountain trails.

A Priestly Box Opened, Contents Intact

Here within are mementos of ceremonies conducted by the priest- mombaki- in past years, items such as betel nuts and sharpened sticks used in killing sacrificial pigs, along with a bundle of miniature tokens of still more killing sticks, too numerous for inclusion full size. Here as well are birds' eggs and river-smoothed pebbles, almost perfectly oval or spherical- chance discoveries believed by the finder to possess an especially potent spirituality. This box also contains- as do a minority of other innama- a small-scale idol called a hipag, thought to be capable of delivering good or evil at the priest's urging.

Kinetic Beings

The idols of the Tinguian (Tinggian, Itneg) People of Abra are usually carved in active poses, in refreshing contrast to the generally static carvings by other Cordillerans. The kinetic Tinguian beings on display thump drums, clang on a gong, noodle on a nose flute, ford a raging river or dance with the fervor of dervishes- even the tribe's scared frog of fertility is shown in the museum dancing (a little).

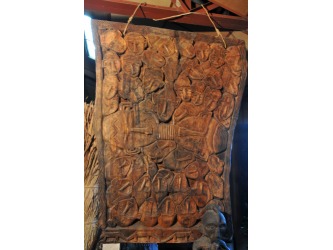

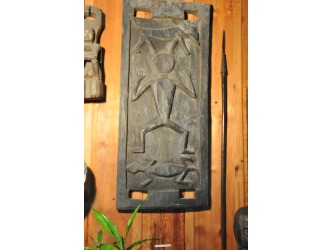

Husband and Wife Burial Plaque

Panegpanan

A clan of Bago Tribespeople, the Bukong's of Bakun, Benguet, installed this figurated plaque within the family's limestone burial cave in about 1910 at the time of the death and interment of the second member of the couple memorialized in the carving. The pair's wooden effigies, embodiments of the spirits, watched over their bones in the cave for nearly a full century until the Bukong's converted to Catholicism (circa 2005), adopted that religion's ancient Egypto-Roman custom of above -ground burial, transferred family skeletons to a concrete vault and sold the panegpanan. Mementos of the cave have come forth in the limestone eyes of the carved couple who, a century on, appear to regard us, in our world of other perils, with a serene indifference common to deities and the dead.

The Tannig Facial Witness (below top left panel): The title given by the artist, Delfin Campol of Banaue, to a large pinewood panel carved in 2002. It groups the the faces of about 45 members (fully in view or substantially concealed) of a tribal wedding party, along with centrally located images of the wedded couple. "The faces signify a happy marriage of the couple": so wrote the artist. The panel's reverse side shows the couple dining quietly at home. They share a big bowl of food, symbolizing prosperity.

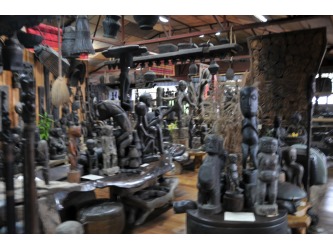

More Images

Below are a few more images of the museum, all these sculptures are awaiting to be moved to their new home, where they will have the space deserved to them. The new museum will be opening its new doors by June 2009. Please take the time to visit this museum to appreciate and partake in a culture that is very magical, indeed. Your view of Ifugao and its' people will be much different when you take a couple of hours to understand how these people have built, maintained and lived in land that is now considered in danger of extinction, but also incredible and so beautiful it is considered

the 8th Wonder of the World.